Reframing European Cultural Production: From Creative Industries towards Cultural Commons

Professor Pascal Gielen (Antwerp University) did research on the biotope around artistic careers, on the role of institutions, and how the transnational creative industries and the longing for a monotopic European identity put pressure on this biotope. Gielen formulates a number of suggestions on how a healthy artistic biotope may be maintained in the future, and how artists can offer us a more complex heterotopic understanding of Europe in a globalising world.

Sustainable creativity

Over the past 15 years, we have conducted studies into artistic selection processes and careers in the arts. Originally, this research focused on contemporary dance and visual art in Belgium (Gielen 2005; Gielen and Laermans 2004; Van Winkel et al. 2012), and was later extended to include a great variety of disciplines, from architecture to theatre and film all over Europe (Gielen and Volont 2014). In 2016, the research was continued in a large-scale interdisciplinary European study on sustainable creativity in post-Fordist cities (2016-2021). Through in-depth interviews, panel discussions, surveys and case studies, 1739 respondents (of which 47% woman and 53% man; 4% younger than 25, 48% between 25 and 54, 4% between 55 and 64, and 1% older than 65; 30% of them have a Bachelor’s, 43% a Master’s degree and 76% of them did a training in art education) in ten European countries were asked more or less the same question: ‘What does it take to build a career, especially a sustainable one, in the long term?’

This quest also brought the role of the institutional context to our attention (Gielen 2014; Gielen and Dockx 2015). Not just institutes for art education, museums and theatres, but politics and even family life have an important influence on a creative career. In the recent developments of the creative industry and creative cities, in which labour is organised on an ever-larger scale and even globally, these institutions find it increasingly difficult to guard the borders between the different spheres of life. This also means that pressure comes to bear on an artistic biotope, which is needed to do creative work in the long term.

In this essay we will begin by outlining this artistic biotope. Then we will describe how the various domains within the biotope used to be protected institutionally in a national context. Next, we will ponder the changing mediating role of institutions. This transformation is partly the result of the transnational policy for the creative industries and creative cities implemented Europe-wide nowadays, based on a global market competition and the longing for a monotopic European identity. These institutional changes put pressure on the artistic biotope. In a final conclusive section, we will, on the basis of recent and still ongoing research, put forward a number of suggestions as to how, in our opinion, a healthy artistic biotope may be maintained in the future too, and how artists can offer us a more complex heterotopic understanding of Europe in a globalising world.

Artistic biotope

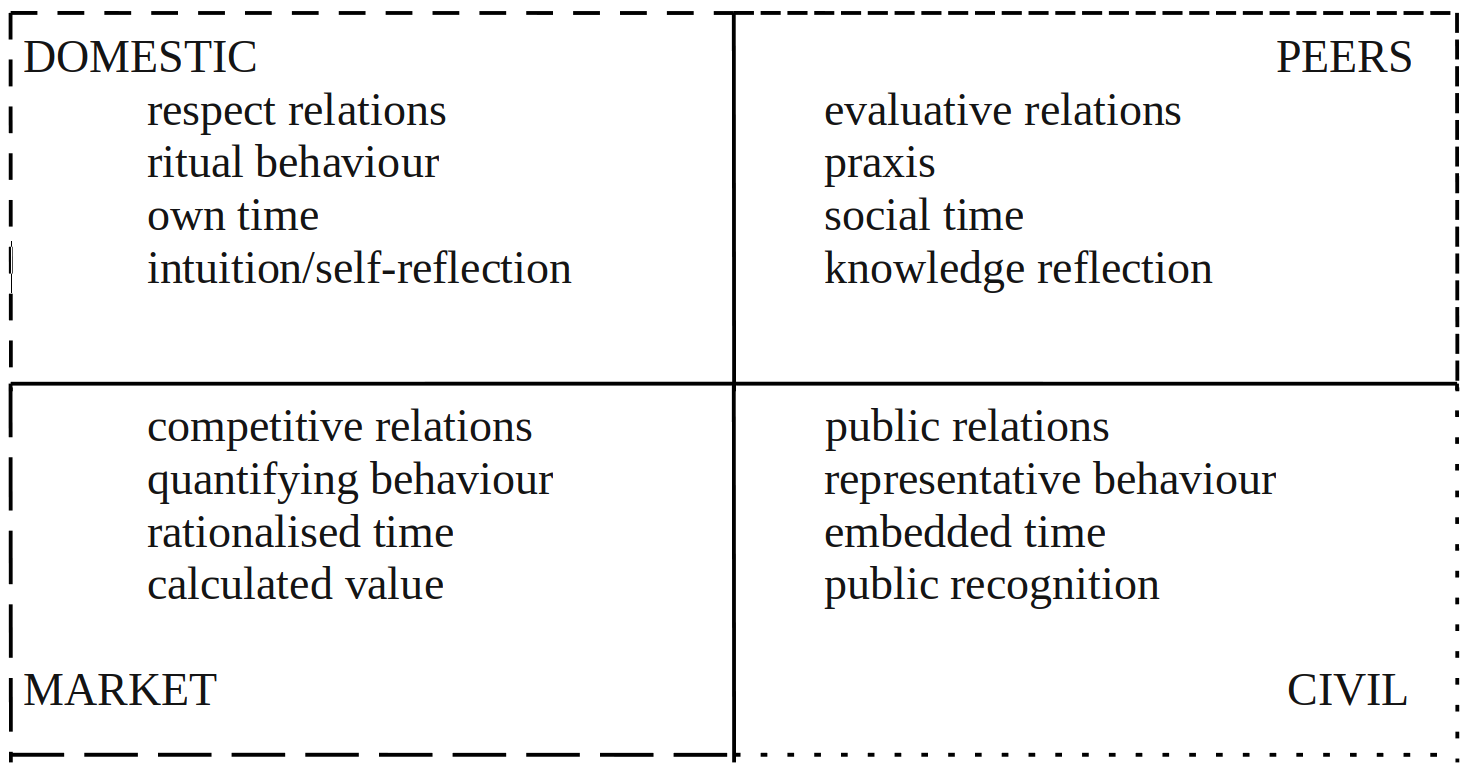

The question of what artists and other creatives need to build and maintain a long-term career received roughly the same answers in various consecutive studies. In the variety of respondents’ answers we were able to distinguish four separate domains into which their requirements can be categorised in an ideal-typical manner (Weber 1904):

- The domestic domain

- The domain of the peers

- The domain of the market

- The civil domain

Subsequent field studies, which included studio visits, in-depth interviews, and case studies, showed that these four domains are very different in terms of (1) social relations, (2) professional behaviour, (3) use of time and how it is experienced and, finally, (4) appreciation or assigning values.

Within the domestic domain, in terms of social relations, for example, the respondents prefer to work in isolation, without being disturbed. Visits to the studio are restricted to an inner circle of spouses or partners, relatives, and friends, especially when it comes to unannounced visits. What is important is that in the domestic domain, when it comes to social relations, intimacy, trust, and respect are the keywords. In interviews many respondents stated that in fact only their partners decided whether a work would even ever leave the studio. If the partner didn’t find a work beautiful, interesting or relevant or even pronounced it ‘bad’, the work was sometimes even destroyed. In other words, partners and other intimate others also guard the borders between the domestic domain and other spaces. With regard to professional behaviour, everyday rituals have an important role in the domestic space. For example, a creative person may first drink two cups of coffee or listen to some music before starting to paint, sculpt, or rehearse. This implies that creatives are masters of their own time and can plan their work according to their own preference. Finally, in the domestic domain much value is assigned to personal judgement, personal taste, intuition, and insight to determine whether an artistic creation actually has any value. Self-reflection and personal experience therefore play an important part in assigning value.

The second domain is that of the peers. This is where (aspiring) artists make their first contact with creative professionals and experts who are knowledgeable about both practical and theoretical aspects of their (future) profession. Obviously, at art academies teachers often fulfil the role of discussion partner and critic, but fellow students can also be important peers. Open studios, workshops or other professional gatherings also make up the domain of the peers. Although here, as in the domestic domain, social relations can be characterised by respect, the evaluative nature of the exchange prevails. Among professional peers, there is a constant evaluation going on. Even when students go and have a beer with a teacher after school, they know that everything they say, each idea they come up with, may be evaluated. This relationship is continued in later contacts with programmers, curators, art critics, et cetera. Among peers, evaluative interactions come first. Behaviour is therefore defined, more so than in the domestic domain, by the active exchange of knowledge, by creating and practising skills, whereby one’s own ability and creative talent are continuously measured against already known skills, already realised creations or against the artistic canon. The domain of the peers is one of research and development, where new ideas and artistic experiments are constantly measured against already existing works or against the knowledge and skills of other professionals. Here, recognition or assigning value is not so much based on self-reflection and intuition, as in the domestic domain, but rather on (historical) knowledge and scientific reflection that are the result of social interaction. It is also the social interactions that define the organisation and experience of time in the domain of the peers. This may vary from an endless debate or a productive discussion during which one loses track of time, to institutionally imposed schedules and contact hours in a classroom. The own time of the domestic space is thus exchanged for collectively determined time in the domain of the peers.

The third domain, where money is all-important, we simply call ‘the market’, albeit in a very broad definition: each time an artistic activity or a creative product is exchanged for money, according to our ideal-typical definition we have a market situation. Therefore, this also applies to governments subsidising the creation of a theatre performance or the organisation of an exhibition. Commercial galleries, art fairs, auctions or the box offices of theatres are of course more obvious marketplaces. The important thing is that in those places social relationships are defined by money changing hands. This is why the art auction is probably the best example of an ideal-typically pure market. At an auction, the only thing that matters is how high an offer is made to acquire a work of art. Bidders can do this completely anonymously and don’t necessarily need to know anything about art or art history. They don’t need to maintain social relationships with artists or other professionals and don’t have to publicly account for their purchase. When buying a ticket for the cinema or theatre, no one will ask us for an extensive motivation – the only thing that counts is paying for admission. The domain of the market in the artistic biotope is primarily defined by financial relationships and quantities. The social relationship is in the first place one between supplier and customer. This means that these relations can be relatively anonymous, which also gives artists a certain freedom, as they don’t have to engage in personal relationship with each individual visitor or collector. In this respect, money ‘liberates’, as already stated in the classic sociology of Georg Simmel (1858-1918) (Simmel [1858] 2011). However, in the domain of the market the creative workers are obliged to constantly quantify their work. Not only do they have to estimate how much money they can ask for their work or how large a buyout amount should be (see, for example, Velthuis 2007), they must also learn to estimate production costs and how to work against a deadline. In short, an important aspect of professional behaviour in the market is the ability to express oneself in terms of quantities, which also applies to the organisation and experience of time in this domain. Time is converted into units and must be calculated as efficiently as possible. Projects with a clear deadline or delivery date are therefore a suitable method for organising one’s work. In the market one cannot afford to lose track of time in endless reflection or introspection, as in the domestic domain, or by having interminable debates, as may happen in the domain of the peers. By contrast, in the market time is strongly rationalised, since time is money. Recognition or assigning value, finally, is expressed in quantitative terms too, such as the price of an artwork or the number of tickets sold, but also the height of production costs or the amount of time spent on making a creative product define the appreciation of a creative work.

The fourth and last domain of the biotope is then the civil domain. Here, social relationships are in the first place public ones. That is, they are visible in a public debate or in an interview or a review in a newspaper or other media. The point is that in the civil domain argumentation and public debate are central. Through argumentation an attempt is made to demonstrate the quality of creative work before a larger public. In arguing the quality, quantity, as in the market, no longer comes first, but rather the artistic, social, and cultural relevance. Such an argument may be that the work is artistically innovating or has a particular social value. Social support is therefore not simply measured in numbers of visitors or consumers, like in the market space. Rather, what is at stake is the broader recognition of an artistic idea or a creative product as a cultural value, without the need to go look at the work or buy it. This means that its recognition goes beyond the borders of the peer domain and also transcends monetary value. A thing only gains cultural value when a number of people use it, for example, to construct their own identity or confirm their social class and culture or subculture (Bourdieu 1984). Within the civil domain creative expressions can also carry political import, as we know from the national canon. In any case, in this last domain artworks can function as references for a collective or wider culture to define its self-worth and identity. This civil space plays also a very important role in building national and European identities. Cultural policies and subsidies or cultural and art education are therefore legitimised by this domain. These arguments are not only to be found in grant applications by artists but also in the policy plans of museums, theatres, biennials, and art festivals. In the civil domain, professional behaviour is no longer exclusively defined by artists who know how to make and defend their work on the basis of (specialist) know-how, as in the domain of peers. Here they also defend the values of the art world or creative discipline they represent to the outside world. In other words, civilly recognised artists assume a public role in which they represent and defend their own support base before a wider, heterogeneous public of politicians, students, journalists and ‘the man in the street’. In order to obtain this recognition, a different time span than that in the other three domains is often involved. Not ‘own’ time, social (professional networking) time or quantified time but social incubation time defines the organisation and experience of time in the civil domain. It is the time of embedding that is required to gain public support. As we know, this may take very long, especially for new or idiosyncratic artistic ideas. In interviews, for example, successful artists and architects spoke of a period of ten years before their work really started to enjoy recognition in society. Prior to that, their work may very well have circulated and be recognised by peers (sometimes even mostly internationally) but not yet in the national media or a national museum or theatre. Civil recognition can take a long time coming and for many artists it simply never arrives. This is also true for artists and designers who are doing quite well commercially. Several of the interviewed creatives make a very decent living from their artistic work. Some artists are even represented by profitable galleries in New York or have no trouble selling their work at the art fair of Basel, even though they are hardly mentioned in the media or have exhibitions in museums. In short, recognition by international peers or the market does not automatically mean social recognition in the civil domain.

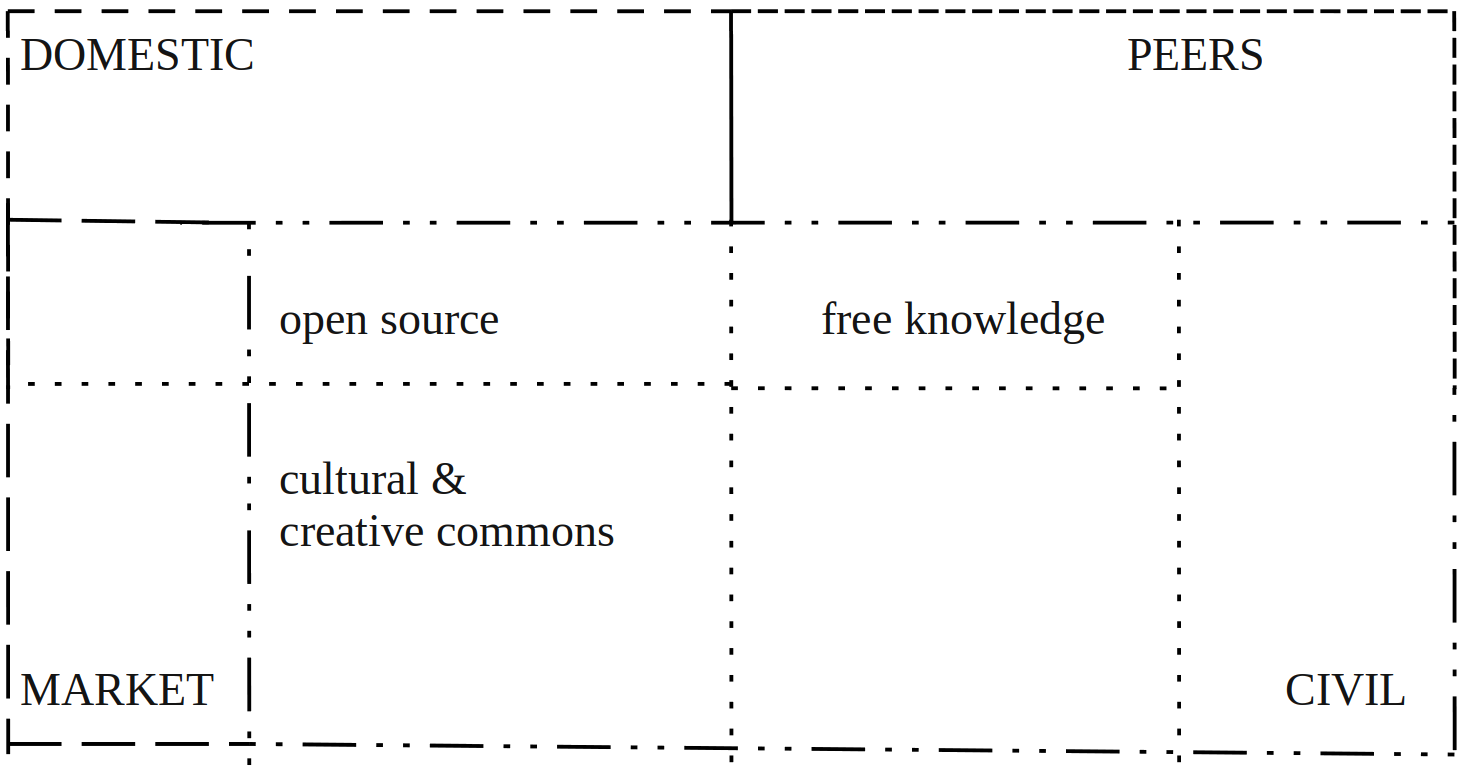

Diagram 1: The artistic biotope

An analysis of creative careers shows that the above biotope is often navigated in the same way. Young creatives produce their first try-outs and experiments in the domestic domain. If they are not self-taught, they then go into art education and gradually integrate into the professional peers domain, and then – sometimes aided by teachers – they may be picked up by a gallery owner (the market) and/or a public museum or art critic (the civil domain). Although there is a certain ‘chronologic’ to this ‘biotope trajectory’, almost all respondents emphasise that at some point in their career a balance between the four domains is important. For example, successful artists who have been in the market and or civil domain for too long, volunteered in interviews that they felt it was high time to return to the peers or domestic domain. Dwelling too long in the market or the civil domain often generates the well-known phenomenon that artists keep ‘endlessly’ repeating an originally good idea simply because it brings them public acclaim and/or economic success. Being able to return to the domestic domain, to the ‘own time’ in order to reflect deeply on their work again, or to the environment of peers where they can in all confidence arrive at new insights through discussions with experts is always deemed necessary, at a certain point in their career, to further develop and deepen their own artistic or creative oeuvre. Reversely, those who keep ‘hanging on’ in the domestic domain will never become professional artists. Art then becomes a hobby or creative therapy, but no creative person can make a living from their artistic work when they remain in the comfort zone of the domestic domain. And also, those who only dwell in the domain of peers run the risk of remaining stuck in endless debates and experiments without ever arriving at an artistic outcome or product. In short, artists who wish to be able to continue to develop their own work in the long run and also wish to make a living from art will continually have to perform a balancing act between the four domains of the biotope outlined above.

National institutional security and its global transformation

When we take a second look at the diagram of the biotope, this time from a more theoretical and macro-sociological angleAs we said before, the diagram of the artistic biotope is an ideal-typical construct based on empirical research. This research consisted mainly of individual interviews and therefore took place at a micro-sociological level. In order to see what role institutions play at the meso level and even macro level other methods are called for, such as case studies, discourse analysis (of policy documents) and sociological theory, and research done by others. Especially when it comes to establishing historical transformations, we could not rely on interviews that were mostly conducted over the past ten years. The analysis laid out in this section is therefore only partly supported by empirical findings. However, these are continuously measured against sociological theories that focus on explaining macro-sociological and socio-historical evolutions. The sociological work of theorists such as Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello (2005) and Richard Sennett (2006 and 2011) has been leading in this respect. In the field of philosophy, the critical theories of Paolo Virno (2004) and Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri (2009), but also the work of philosopher and educator Gert Biesta (2013) provided us with the most accurate interpretive frameworks (see also Gielen and De Bruyne 2011; Gielen 2013; van Heusden and Gielen 2015)., we can draw at least two conclusions. First, we may assume – and this is frequently stated by respondents in the interviews – that the outlined domains enjoy, or at least did enjoy, some form of collective or institutional protection, often on a national level. From interviews, documented artists’ biographies and sociological studies (Adams 1971; Bott 1957; Weeda 1995) we may infer that, for example, the traditional family structure is crucial during the first professional years of creative individuals. After all, much trial and error doesn’t pay many bills and older respondents readily admit that during the first five or even fifteen years of their career they were in fact living off the income of their partner. But the institution ‘family’ is not only important for financial reasons. Partners also provide mental support, often a crucial element in the developmental phase of creatives. During their start-up and experimentation stage creatives can have serious self-doubt and often have to deal with disappointments. In short, in the domestic domain both own time and intimacy are institutionally protected by the family. But as we know, this traditional family structure started to erode substantially since the 1970s. The number of divorces and single-parent families has grown tremendously over the past forty years. A changing labour market, which not only welcomed more women but also placed higher demands on mobility and flexibility (see, for example, Zaretsky 1977; Sennett 2006 and 2011) started to take its toll on the private sphere and therefore on family life. Especially creative labour – which often means precarious project work and expects increasingly international mobility in a globalising cultural industry – is hard to combine with traditional family life (Gielen 2009 and 2013). All this contributes to the decline of the institutional protection of the domestic domain.

The same can be said for those institutions that have traditionally played a protective role for the peers domain or the civil domain. Especially after the Bologna Declaration, universities and academies in Europe came under pressure from international competition. It’s one of the reasons they have grown in scale over the past ten years. They have merged with other educational programmes and have strongly rationalised educational space and time through measures such as strict contact hours and competencies (see, for example, Biesta 2013; Gielen 2013). And although this may have increased the efficiency of education, it has made it increasingly difficult for our education to safeguard its characteristic social time for debate and trial and error. A similar analysis can be made for national museums, theatres, art critique, and other public art institutions in the civil domain. The continuing global economic crisis is not only causing subsidies and political support for such institutions to cave in. Within a globalised cultural industry, both cities and art organisations are increasingly forced to compete against each other. Cultural and creative cities try to survive in an economic sense or enhance their position (Nowotny 2011; Gielen 2013). In this competition, economic value is mistaken for cultural value, just as visitor numbers are mistaken for a social support base. As a result, institutions no longer, or do less so, protect the incubation time for the social integration of artistic work. Fewer art reviews in the national mainstream media also mean that artists have fewer public platforms, making it increasingly difficult for them to realise their public role (Lijster et al. 2015).

At first glance, it seems like the current tendencies of globalisation are reinforcing only one institution, i.e. that of the market. At least at the European policy level we see that European citizenship, culture, and education since the Lisbon Council of Europe in 2000 are understood as a means of making the Union the most competitive and dynamic economy of the world (Biesta 2011). The market with free mobility of goods, money, and people was already seen from the very beginning, after World War II, as the foundation of its politics and institutions. Official cultural policy on the European level is seen in the first place as an economical tool for welfare improvement (Minichbauer 2011).

Encouraged by this European official policy, the borders of the other domains of the biotope are less institutionally protected and the logic of the market does intrude in these domains more than before. As a result, an important quality of the market, namely the ability to quantify one’s own creative labour and results, is now being integrated in the other domains. For example, we learned from interviews with architects that they are increasingly using design software in their studios that monitors risks and feasibility, also in a financial sense, already during the creative process itself. This means that the creative process is already quantified and formatted in its initial stages. Also, the global advent of Internet access in the home enables creatives to move from the initially domestic space into other domains with ease. For example, from the studio one can chat with one’s peers about artistic work at an early stage, or put work on offer on the market, virtual or otherwise. Many respondents said that nowadays they use the Internet to maintain social networks, both with peers and the market, as well as in the civil domain. In any case, email and other virtual communication appear to hold great attraction. Some of the respondents said that they consciously banned the computer (and especially the Internet) from the studio, precisely because it was a constant threat to their concentration, and also invaded their ‘own time’ and intimacy.

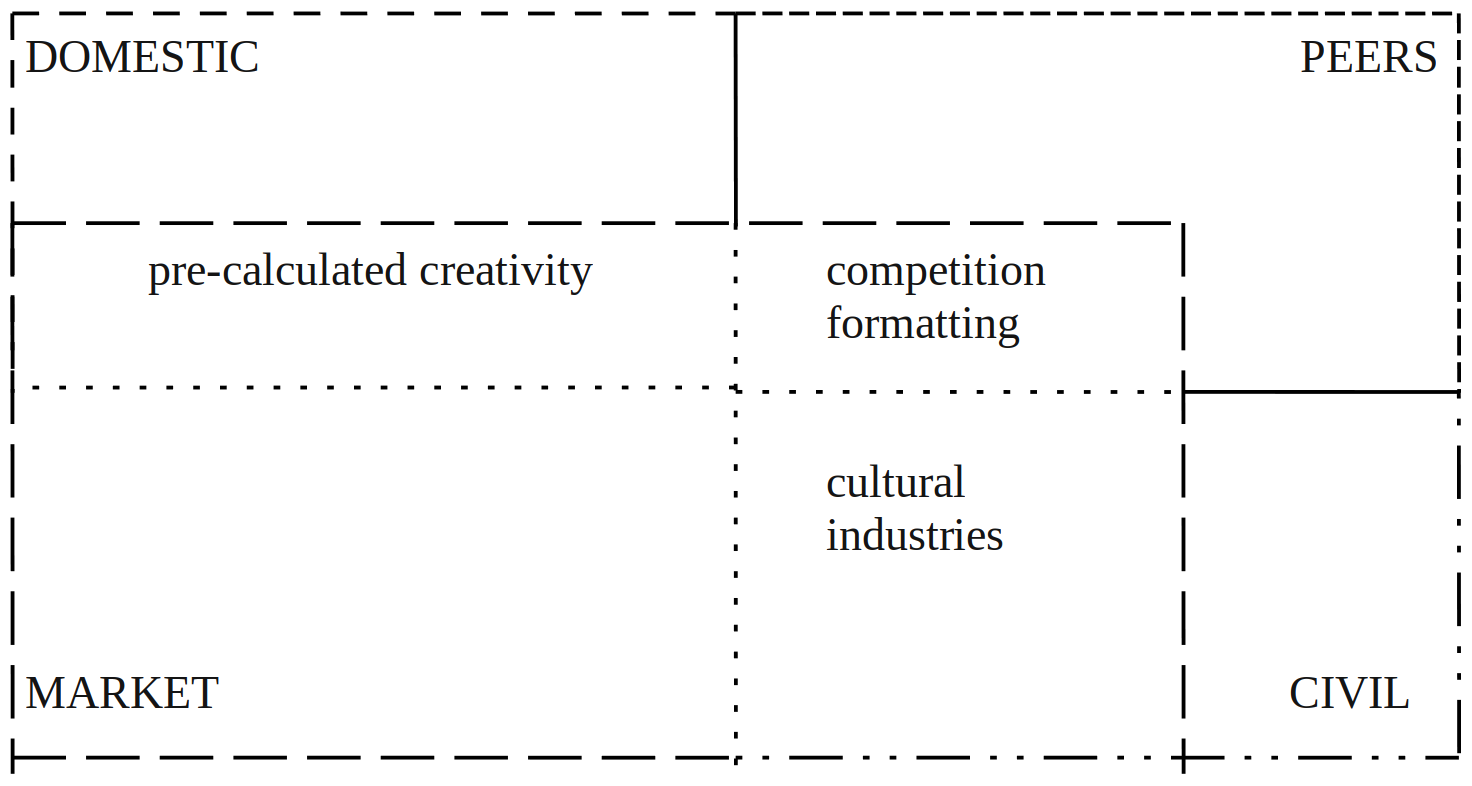

In the domain of the peers the quantification logic of the market intrudes via, for example, the rationalisation of the educational space, via the Bologna Declaration in Europe, as stated before. Contact hours, competencies, the duration of studies and all the concomitant monitoring in the form of accreditations and audits alter the relationship between student and teacher and interfere with the social time for debate and knowledge exchange (Biesta 2013). Besides, the competition between teachers and students and among the students themselves is being fuelled by contests, teamwork, (Sennett 2011) and by agencies within the schools aimed at ‘marketing’ the students even before they graduate. In the civil domain we see how institutes such as museums and theatres also tend towards a logic of quantification. For example, visitor numbers are meticulously kept and become more and more decisive in making artistic choices and legitimising policies. In the case of governments giving subsidies, the emphasis is more and more on the number of venues played and on how much income (including that from ticket sales) is generated by the artists or institutes themselves. This strongly encourages national museums and theatres to orientate themselves on international art tourism or the cultural industry. Diagram 2 illustrates how this expansion of the market space – again, encouraged by European policy – installs hybrid zones in which the values and logics of various domains start to intermingle. The already noted confusion of visitor numbers with public support in the overlap between the market and the civil domain is but one example of such a zone. Courses in cultural management and artistic entrepreneurship in which students learn how to calculate their creative talent and measure it against the potential market value in advance, are expressions of another hybrid zone in the fusion of the market and the domain of the peers. With its heterogeneous zones, diagram 2 therefore illustrates the paradigm of the creative industry in which creativity is not only quantified, measured and formatted, but is also assigned a well-demarcated district in creative cities.

Diagram 2: The artistic biotope in the creative industries paradigm

Feedback

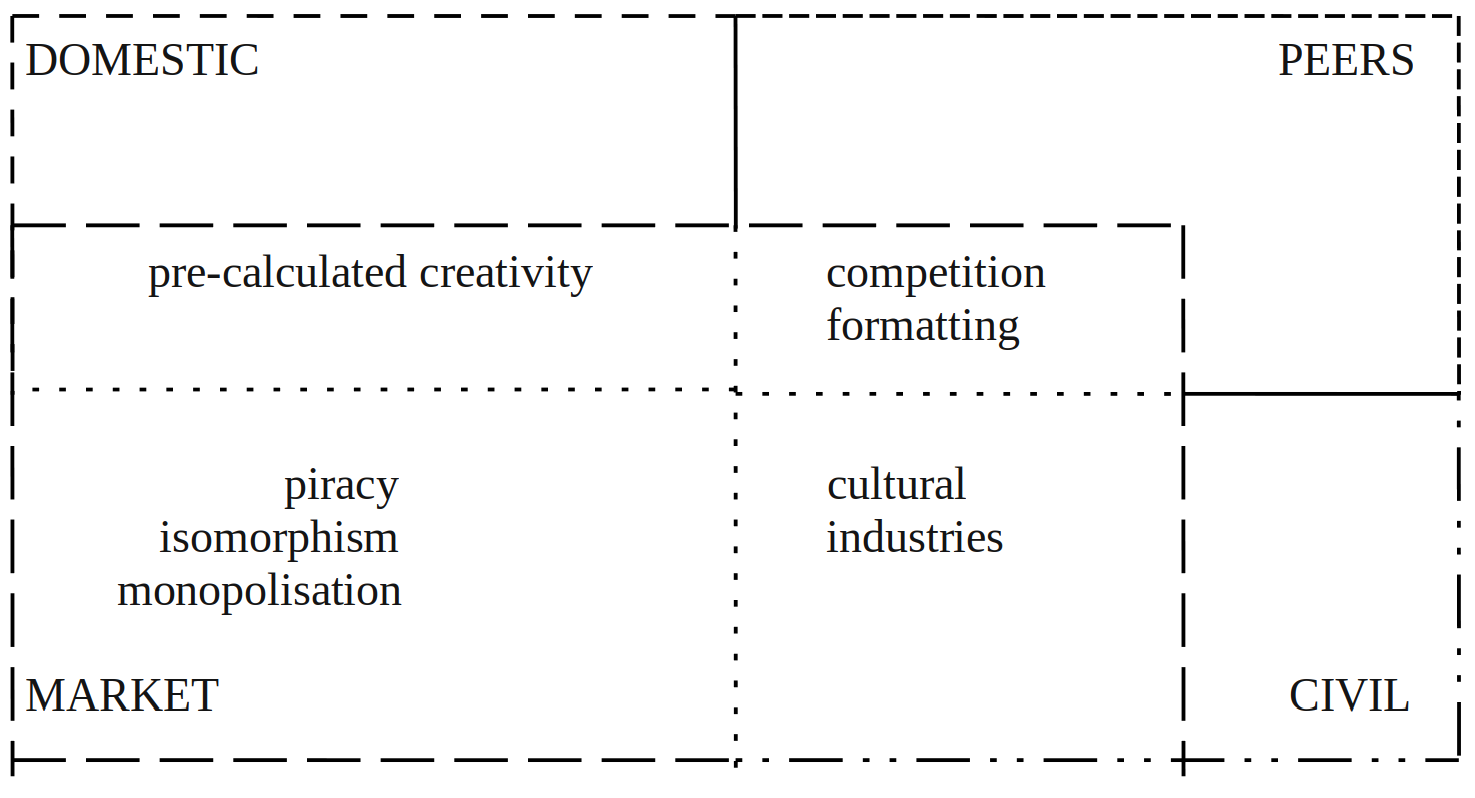

Worth noting in this is that a market that imposes its quantitative logic onto other domains, thereby also begins to transform itself. This is why we stated in the preceding section that ‘at first sight’ only the institution of the market was reinforced. As it is, the expansion into other domains also generates a remarkable feedback to the market domain. A traditional free market that is governed by the rules of supply and demand and by free competition begins to undergo a transformation because of this. For instance, illegal downloads, hacking, and piracy are known and even frequently occurring practices amongst the creatives we interviewed. From their presumably safe place in the domestic domain the respondents are frequently navigating the fine line between creativity and petty crime in order to expand their creative horizon. However, such practices are known to be dysfunctional to the traditional functioning of the market. They at least disrupt the relation between supply and demand. The tendency to quantify, formalise, and standardise education in turn stimulates the homogenisation of cultural products in the market. In combination with the encouragement of competition among students this leads to increasingly competitive isomorphism in the market (DiMaggio 1991): artistic and creative products, including festivals and biennials, are beginning to look more and more alike because they are constantly comparing and mirroring each other. In any case, not just the artworks but also the artists themselves who are presented there seem to be becoming more and more interchangeable.

At the European level this evolution to homogenisation is again encouraged by defining the European territory as a monotopic market of interchangeable cultural capitals and creative cities. In any case, in the past decade in Europe, the dream of a common market with free competition and frictionless mobility has turned into a problematic political name-calling, troikas, and barbed wire. In particular the use of troikas such as in Greece are evidence of the belief that unity within the European Union can be achieved or restored by fixing the economy, that mutual trust can be gained by balancing budgets. In this belief, the European territory is seen as a monotopia in which the competition between (creative) cities, regions, and countries benefits everyone. Until recently, no one would have dared to predict that this European utopia might very well turn into a dystopia of reactionary divisive politics and exits. Nevertheless, social geographers Ole Jensen and Tim Richardson neatly pointed out, as early as 2004, that a policy of competition between cities, regions, or countries might raise the common prosperity, but would also always generate winners and losers. No matter how relative differences may be, the inherent logic of competition is that it creates a hierarchy of at least gradual inequalities between those who have more and those who have less. Those who see the free market as the foundation of Europe apply the same measure to all residents, cities, regions, and countries, looking only at their differences in quantitative terms. From that perspective there are only actors who do better or not so well, who are very successful or do very badly. Then there are only front runners and stragglers and everyone in between, but everyone is going in the same direction, towards the same worthy goal. That goal is after all easy to calculate and can be expressed in numbers. Within Europe, this leads to the ironic but rather apt spectacle in which glances are mostly cast from down to up, or from the geographical south to the north. At the moment, in Europe fierce competition inevitably leads to envy and exclusion, along with the occasional foul play. The fundamental problem of Europe on the cultural level is the belief that cultural differences can be smoothed over by making everything mutually comparable in exchange value. And this we finally can also detect in the last domain: the civil space. The partial ‘occupation’ of the civil domain also produces curious effects in the market. Within the paradigm of the cultural industry more and more artistic clusters and chains of private institutions are formed (for example Guggenheim or the majors in pop music), which leads to monopolies. As we know, monopolies also form a threat to traditional markets. Diagram 3 sketches the situation in which not only the institutional grip on the domestic domain, the peers domain and the civil domain is loosened, but also that on the domain of the market. In our view, this represents what the global terrain of artistic and creative production looks like today.

Diagram 3: Feedback in the creative biotope

The above diagram illustrates how traditional, mostly national, institutions are having trouble protecting their institutional borders. Encouraged by a European policy, this results in changes in the relationships, professional attitudes, experiences of time and recognition (of quality) within each domain. Grey, or rather, hybrid and heterogeneous zones arise in which the logics of different domains and various institutions begin to intermingle. This macro-sociological shift and hybridisation doesn’t alter the fact that individually, the interviewed creative workers and artists still distinguish between the various domains on the micro-sociological level. Also, they deem a balance between the domains necessary if they are to survive artistically in the long run. However, the point is that this balance is less and less guaranteed or enforced institutionally. On the contrary, finding the right balance is increasingly seen as an individual responsibility. Drawing borders between work and private life, between the market or civil domain and the domestic domain, is a task that has come to rest squarely on the shoulders of the individual. The artist, the creative worker – often a freelancer – decides individually when to close the laptop. In a competitive atmosphere at school, a student makes a personal decision whether or not to measure a still fresh artistic idea against the opinion of fellow students or teachers, or to keep it private and thereby safe (because it is then protected against ‘theft’). And in the civil domain the creative must individually decide whether to resist the pressure from a museum director (or subsidising government) who is only interested in showing work that draws a public (because it is already known) or to stubbornly persevere and choose to present little-known or not yet recognised work. Collective responsibilities are increasingly shifted towards the individual, bringing more and more pressure to bear on creatives. This leads to well-known post-Fordist anomalies: stress, burnout, depression, and dropout. We have seen it all in the course of our frequent research visits, studio visits and in-depth interviews. It was one of the reasons why we set up a new study to specifically focus on the issue of sustainability and the role of the artistic biotope in this respect (see CCQO.EU). In what follows a number of hypotheses as tentative conclusions of this study are articulated.

Creative commons

In interviews with artists and creative workers, the same complaints often came up. When asked why a respondent came under pressure or suffered from a burnout, they pointed at more or less the same causes: increasingly shorter deadlines, resulting in too little time for development and experimentation, and heightened competition with fellow artists, which not only eroded trust and solidarity but also led to less exchange of knowledge and information among professionals. Schematically, these complaints were included in diagram 3, where the growing free-market system generates all sorts of effects in domains whereas this didn’t occur, or at least occurred less, in the past. And, as we said, in the end this has a relatively disrupting effect on the traditional operation of the market itself. The situation makes respondents sometimes cast a ‘nostalgic’ look at diagram 1, where the domains are still neatly delineated and protected by national institutions. We call such utterings ‘nostalgic’ because they primarily look back at an idealised – and mainly Western – art world as it was in the first half of the twentieth century. In this image the (bourgeois) family is represented as a safe haven, royal and national art academies as friendly environments where one could debate and experiment until late at night, and museums, philharmonic orchestras, national operas, and theatres protected the (mostly national) art canon and cultural hierarchy. Most likely, this ideal world never really existed. Nevertheless, we may surmise that in those days of nation building the domains within the biotope were better protected than today. Our hypothesis, however, is that a restoration of national institutions in that vein is hardly likely. Whatever subsidising governments there were, over the past decade they appear to be mostly making cutbacks in educational and cultural spending, making it difficult for (national) institutions to protect the peers concerned and the civil domain. Likewise, it is very doubtful whether the traditional family structure will be fully restored any time soon. This doesn’t take away from the fact that the creative professionals, often working as freelancers, are in need of collective protection. Anyway, during interviews this was mentioned frequently. Sometimes, solutions were sought in, literally, ‘collectivisation’. Artists then form collectives in which they share materials and studio space as well as social contacts, thereby cutting costs. In some cases this even leads to more complex systems of solidarity in which participants in, for example, cooperatives set up an alternative health insurance and provide other forms of social security. In order to interpret these young, sometimes still budding initiatives we use the notion of the ‘commons’. This concept has gained prominence both in recent philosophy (Hardt and Negri 2009) and in law research (Lessig 2004). According to Hardt and Negri, guaranteeing such a commons is necessary to safeguard future creative production. These philosophers have described the commons as a category that transcends the classic contrast between public property (often guaranteed by the state) and private property. In the area of culture, Negri and Hardt mention knowledge, language, codes, information, and affects as belonging to the commons. This shared and freely accessible communality is necessary to keep the economy running in the long term, to regain the balance in the ecological system, and to keep our cultural fabric of identities dynamic (Hardt and Negri 2009: viii).

It is because of this importance of the commons that our recent research focuses on this aspect, especially on concrete forms of organisation or even institutions that can support and protect these creative commons. So far, our explorations have led us to civil initiatives originating in the wasteland between market and state, between commercial value and political-cultural value. Especially after the financial crisis, artists have sought and continue to look for a way out through alternative forms of self‑organisation and collective solidarity structures. One example of this we find in the music world in Amsterdam, where fifty composers and musicians have joined forces in order to acquire and collectively manage a former bathhouse in the city centre as a music venue. Splendor, as the organisation was named in 2010, has no hierarchic management, no PR or programmer, no public funding and no free market mechanisms either. In the tradition of the Do-It-Yourself culture the artists simply do everything themselves and have meanwhile established a broad audience for not always evident and sometimes also experimental new music. These fifty artists share responsibility for all aspects of the cooperative institute. Its financial structure consists of a modest one-time contribution (1000 euro per artist), bonds that were issued, and subscription fees of 100 euros per year providing access to membership concerts. Since the agenda of the venue provides playtime for all, a grassroots-democratic programming is assured in a simple manner, guaranteeing full artistic freedom for all. The curious thing is that the fifty participants have never physically held a meeting, neither for the establishment or management of the organisation nor for the programming. This means that the board relies completely on mutual trust and in its by now eighth year of operating that trust has hardly ever been betrayed. All this makes Splendor one of the examples of new art institutes that organise themselves according to the principle of the commons (Ostrom 1990; De Angelis 2017). All over Europe similar developments can be noted in which civil initiatives create their own third space between government (or state) and assemblies. Following constantly recurring bottom-up organisational principles, such as a grassroots‑democratic decision-making structure, a horizontal organogram, self-governance, peer to peer consultation, and assemblies, an age-old principle of shared use of common ground is given new life (Gilbert 2014).

At Splendor this collective management – following one of the design principles for the commons as defined by economist Elinor Ostrom (1990) – is done by a relatively closed and homogeneous group with a shared culture. Other cultural organisations try to break open this relative seclusion by following the commoning principles as developed by political economist Massimo DeAngelis (2017) and others. Here, following radical democratic principles of inclusivity, the aim is to give access to cultural goods and their production to anyone, regardless of social class, age, nationality, gender, religious persuasion, and so on. One example of this is the impressive venue Ex Asilo De Filangieri in Naples, where weekly assemblies determine how a landmark cultural building is used. The result of this decision-making structure is that the studios and rehearsal spaces are used by both local carnival clubs and renowned theatre directors. All those who participate in the assembly are allowed to co-determine the organisation’s functioning and programming. The Spanish architectural studio Recetas Urbanas takes that grassroots-democratic commoning principle even further by providing its designs for free on the Internet and by actively inviting, in their interventions, collaboration with those who are not yet being represented (by politics, unions, NGOs or organised social interest groups). Prisoners, people with disabilities, drug addicts, refugees, illegals, Roma, and so on, who are neglected by representative democracy – often having literally and legally no voice or right to vote – are given the opportunity to still have an impact on society through collaboration in building projects. In that sense, the commoning practice of these artistic and creative organisations, in line with Jacques Rancière, is always also political: they render visible what was until then invisible. According to this philosopher, every political act is aimed at a rearrangement of that communal visible space. In relation to this he speaks of the common basis of art and politics as ‘the sharing and (re)distribution of what can be perceived with the senses’ (partage du sensible). This is the aesthetic moment of politics, but also precisely the ‘political of art’, in that it is capable of showing what had been neglected until then. Art can make us aware of voices that we did not hear before, of political emotions and interests that suddenly acquire a public face (Rancière 2000; Gielen and Lijster 2015).

Splendor provides self-governance for the bottom layer in the creative chain, especially the artist. L’Asilo and Recetas Urbanas attempt to uncover neglected cultures from the bottom up, time and again. Whereas with Splendor it is done by a limited number of ‘initiated’ from the same art discipline. L’Asilo attempts to reach out to everyone who wishes to organise cultural activities in the city, according to grassroots-democratic principles. By doing this, at Splendor they may be rewriting music history but this re-articulation remains the privilege of a relatively exclusive group of commoners. L’Asilo and especially Recetas Urbanas are opening the door to a much more permanent cultural recalibration.

The three examples all focus on those who are not yet being represented; those who are at the bottom of the symbolic or economic ladder or have very little power over making decisions. That’s why their practices can be called constitutive and their organisations can be called constitutions instead of institutions. They share the aspect that they are trying to provide firmer ground to that or those who do not yet have it, to those whose voices are not really heard or those who are not yet represented. In Dutch, the word for ‘the constitution’ is grondwet (literally ‘ground law’) containing the prefix grond (ground, soil, bottom, base). The fact that this operation is done through communal decision-forming processes also supports the choice for the term ‘constitutions’. The prefix ‘con’ is a reminder of its collective character. Finally, Splendor, L’Asilo, and Recetas Urbanas operate in a civil domain between market and state for which very little is legally regulated so far. Commoning art organisations therefore frequently find themselves in the same position as the founding fathers of the constitution. The philosopher Hannah Arendt once said about them:

… those who get together to constitute a new government are themselves unconstitutional, that is, they have no authority to do what they have set out to achieve. The vicious circle in legislating is present not in ordinary law making, but in laying down the fundamental law, the law of the land or the constitution which, from then on, is supposed to incarnate the ‘higher law’ from which all laws ultimately derive their authority (Arendt 1990, 183–84).

Whereas Splendor made the conscious decision not to apply for public funding as it does not wish to play according to the rules of the government (and the Dutch Performing Arts Fund), Recetas Urbanas calls its field of operation ‘a-legal’. Ex Asilo Filangieri produced its own Declaration of Urban, Civic and Collective Use for the commonal running of its venue in Naples. This declaration was later adopted by the city authority and thereby also became applicable to other civil initiatives. In addition, both Recetas Urbanas and L’Asilo often rely on the national constitution to defend and legitimise their activities and self-regulation (De Tullio 2018, 299–312). After all, many national constitutions already guarantee commonal principles such as the democratic use of and free access to basic community goods and services (such as education, culture, work, healthcare), inclusivity, equality, and the right of self-governance. Constitutions were, in most cases, drawn up by people who once fought for commonal principles themselves, such as autonomous government, equality, and mutual solidarity for the people of, in those cases, nation states.

On our explorative research trip, we encountered a growing number of artistic initiatives that generate completely different forms of working and organising. Despite their great diversity, what all those initiatives such as Splendor, L’Asilo and Recetas Urbanas, have in common is that they are built within the civil domain. That is to say, they all start with a civil initiative for which a government has not or not yet designed regulations or subsidies and that is not or not yet of commercial interests to a free market. This is why in diagram 4 we present them as an expansion of the civil domain. From there they trickle into the domestic domain (for example, open source projects such as Wikipedia and Linux) where they make free knowledge and free creative tools available. They generate free knowledge by launching debates and sometimes activist discussions in art academies, during artist-in-residencies and open studios where they analyse their social position from an economic, political and social perspective, as well as from an ecological perspective. In addition, they penetrate the market itself by introducing alternative economies (via, for instance, cooperatives) and alternative laws (such as the already mentioned Creative Commons licence) (Lessig 2004).

Diagram 4: The creative commons biotope

The organisations we have so far encountered in the domain of the Commons not only have in common that they all originate in civil initiatives. What is often also striking, is their highly heterogeneous configuration. They not only develop, simultaneously, activities in the most divergent fields, such as architecture and fashion and education and visual art, they also freely mix formal and informal relations, public and private, politics and labour in how they are structured. Just as in mixed farms or the traditional circus, family relations and friendships are combined with professional roles, and commercial and civil activities merge into each other to the point that they can no longer be distinguished. Also, whereas many services are exchanged for free, others are strictly regulated and formalised in contracts. Precisely because of this heterogeneity these new institutions of the commons lend themselves to further study. Our hypothesis is that their organisational form may be more suited to the creative labour model in which individuals are involved as a whole. In relation to the biotope we have outlined, we could also say that these institutions of the commons attempt to solve the issue of the balance between the various domains internally through mutual agreements and a division of tasks. To illustrate this with a concrete example: when one artist ‘works the market’, another artist within the same organisation has time and space to experiment and develop new work, since the latter is temporarily exempt from earning money, through a system of reciprocity. It is evident that social relations or the collectivisation of activities make it possible to establish a new balance within the biotope, while also allowing oneself a more independent attitude towards external, traditional institutions such as an art academy, a museum or an auction, or even a government. In any case, the collective labour model provides better opportunities and also more security than the dominant freelance model of the creative industries. After all, this latter, post-Fordist model only pays for production time, while other things the creative worker needs to be able to produce at all (such as education, time to experiment and to develop) are being shifted more and more to the individual level. By contrast, a collective and heterogeneous labour model tries to meet these needs, which lie outside the sphere of labour and the market.

The potential advantages of these organisations of the commons do not prevent them from running into certain problems. For example, the typical hybridity can also carry the seed of dysfunctions we are familiar with from traditional mixed (family) businesses, such as nepotism and fraudulent tendencies. And such organisations are not only threatened from the inside, but from the outside as well. Civil self-organising makes it easy for governments to relieve themselves of public tasks that were initially theirs. Governments may find it easy to ignore their cultural and educational responsibilities, if these tasks are already spontaneously taken care of by volunteer initiatives. However, less government involvement also means that it becomes more difficult to develop a broader social support base in the civil domain. Organisations of the commons are therefore at risk of becoming relatively closed peer communities of insiders or ‘connoisseurs’. In addition, commercial parties can then pass on a large part of the labour costs to these commons and only reap the lucrative benefits. Commons organisations have always run the risk of attracting ‘free riders’ (Ostrom 1990), individuals or organisations trying to walk away with the profit without investing in the commons proportionally. Further research will have to reveal what are the values and traps of these new artistic and creative labour models. What, for example are fitting legal and political conditions for an optimal functioning of the institutions of the commons?

As long as futurology is not an empirical science, it will be hard to predict whether this advent of the commons will continue. And therefore the question whether the new institutions of the commons will replace or complement the traditional private and public art and (national) cultural institutions, will remain unanswered for now. But their observed potential for re-balancing the artistic biotope and for generating more sustainable creative labour makes further research necessary, to say the least. It may even be our scientific and civil duty. But we see it also as the duty of European policy to give research about and testing of the commons at least a chance. Rethinking and developing new legal and economic models seems to us the main political task of a region that nowadays easily can draw lessons from its monolithic orientation on global economy and the free market. The colourful multitude of singular artistic and cultural initiatives we met in the commons teaches at least that this restricted orientation neglects a divers and heterotopic potential to rethink human relations of exchange within Europe and its global relationships with the world. To safeguard culture and its multitude of identities assumes at least that we not only look at its economic side, for instance by encourage creative industries in a free market, but also and probably more so that we develop and stimulate a strong civil society where our human creative commons can take up a pivotal position between a global market and a national state.

Originally published under the title ‘Saveguarding creativity: an artistic biotope and its institutional insecurities in a global Market orientated Europe’, in the Handbook of Cultural Security, by Watanaby, Y. (edit.), published by Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing in 2018 (ISBN 978-1-78643-773-0), 398-415.

Reprinted by permission of the Author.

Copyright: the Author and Edward Elgar Publishing

References

Bal, Mieke. 2006. “Exposing the Public” in A Companion to Museum Studies, edited by Sharon Macdonald, 525–542. Malden, Oxford and Victoria: Blackwell.

Biesta, Gert. 2013. The Beautiful Risk of Education. Boulder and London: Paradigm.

Biesta, Gert. 2011. Learning Democracy in School and Society. Education, Lifelong Learning, and the Politics of Citizenship. Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, Boston & Taipei.

Boltanski, Luc, and Eve Chiapello. 2005. The New Spirit of Capitalism. London and New York: Verso.

Bott, Elizabeth. 1957. Family and Social Network. New York: Free Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1995. The Rules of Art. Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Dockx, Nico, and Pascal Gielen, ed. 2015. Mobile Autonomy. Exercises in Artists’ Self-Organization. Amsterdam: Valiz.

DiMaggio, Paul, and Walter Powell, ed. 1991. The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis edited by Walter Powell. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gielen, Pascal, and Rudi Laermans. 2004. Een omgeving voor actuele kunst. Een toekomstperspectief voor het beeldende-kunstenlandschap in Vlaanderen. Tielt: Lannoo.

Gielen, Pascal. 2005. “Art and Social Value Regimes”, Current Sociology 53 (5): 789–806.

Gielen, Pascal. 2009. The Murmuring of the Artistic Multitude. Global Art, Politics and Post-Fordism. Amsterdam: Valiz.

Gielen, Pascal, and Paul De Bruyne, ed. 2009. Being an Artist in Post-Fordist Times. Rotterdam: NAi.

Gielen, Pascal. 2010. “The Art Institution in a Globalizing World”, The Journal of Arts Management, Law and Art Institution in a Globalizing World, 41 (4): 451–468.

Gielen, Pascal. 2013. “Artistic Praxis and the Neoliberalization of the Educational Space”, Journal of Aesthetic Education

Gielen, Pascal, ed. 2013. Institutional Attitudes. Instituting Art in a Flat World. Amsterdam: Valiz.

Gielen, Pascal, and Louis Volont. 2014. Sustainable Creativity in the Post-Fordist Condition. Groningen: University of Groningen (internal report).

Gielen, Pascal, and Thijs Lijster. 2015. “Culture: The Substructure for a European Common” in No Culture, No Europe. On the Foundation of Politics, edited by Pascal Gielen. Amsterdam: Valiz.

Gielen, Pascal. 2016-2021. Odysseus Research Project: Sustainable Creativity in the Post-Fordist City. Brussel/Antwerp: Fund for Scientific Research Flanders/Antwerp University, https://www.uantwerpen.be/en/research-and-innovation/research-at-uantwerp/funding/flemish-funding/fwo/odysseusprogramme.

Foucault, Michel. 1998. Aesthetics. Essential works of Foucault. 1954-1984. London: Penguin Press.

Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. 2009. CommonWealth. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Hetherington, Kevin. 1997. The Badlands of Modernity. Heterotopia & Social Ordering. London, New York: Routledge.

Lessig, Lawrence. 2004. Free Culture. How Big Media Uses Technology and the Law to Lock Down Culture and to Control Creativity. New York: The Penguin Press.

Lijster, Thijs, Suzana Milevska, Pascal Gielen, and Ruth Sonderegger. 2015. Spaces for Criticism. Shifts in Contemporary Art Discourses. Amsterdam: Valiz.

Minichbauer, Raimund. 2011. “Chanting the Creative Mantra: The Accelerating Economization of EU Cultural Policy” in Critique of Creativity. Precarity, Subjectivity and Resistance in the ‘Creative Industries’, edited by Gerald Raunig, Gene Ray and Ulf Wuggenig, 147–163. Mayfly: London.

Nowotny, Stefan. 2011. “Immanent Effects: Notes on Cre-activity” in Critique of Creativity. Precarity, Subjectivity and Resistance in the ‘Creative Industries’, edited by Gerald Raunig, Gene Ray and Ulf Wuggenig, 9–21. Mayfly: London.

Ostrom, Elinor. 1990. Governing the Commons. The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jensen, Ole B., and Tim Richardson. 2004. Making European Space. Mobility, Power and Territorial Identity. London & New York: Routledge.

Sennett, Richard. 2006. The Culture of New Capitalism. London: New Heaven.

Sennett, Richard. 2011. The Corrosion of Character: The Personal Consequences of Work in the New Capitalism. New York: Norton.

Simmel, Georg. (1858) 2011. The Philosophy of Money. London & New York: Routledge.

van Heusden, Barend, and Pascal Gielen, ed. 2015. Arts Education beyond Art. Teaching Art in Times of Change. Amsterdam: Valiz.

Van Winkel, Camiel, Pascal Gielen, and Koos Zwaan. 2012. De hybride kunstenaar. ’s-Hertogenbosch: Expertisecentrum Kunst en Vormgeving, AKV/St. Joost Avans Hogeschool.

Velthuis, Olav. 2007. Talking Prices. Symbolic Meanings of Prices on the Market for Contemporary Art. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Virno, Paolo. 2004. A Grammar of the Multitude. Los Angeles and New York: Semiotext(e).

Weber, Max. [1904] 1949. “Objectivity in Social Science and Social Policy” in The Methodology of the Social Sciences, edited and translated by Edward A. Shils and Henry. A. Finch. New York: Free Press.

Weeda, Iteke. 1995. Samen Leven. Een gezinssociologische inleiding. Amsterdam: Stenfert Kroese.

Zaretsky, Eli. 1977. Gezin en privéleven in het kapitalisme. Nijmegen: SUN.