ETMAC: The Extra-territorial Ministry of Arab Culture

At a time when Arab countries are bleeding away their creative capital with the departure, emigration, or exiling of pioneering intellectuals and artists, one wonders about the future of their practices and legacies. HaRaKa’s performance theorist and artist Adham Hafez and anthropologist and urbanist Adam Kucharski pose the following question: can the institution of the ministry of culture be rehabilitated to serve this new diffuse community of art producers and serve as a locus of cultural production outside of the traditional boundaries of the nation? Can the institution evolve to meet the needs of an artistic and cultural community that is, at least temporarily, extra-territorial? And can it help to rebuild shattered national institutions on artists’ terms?

ETMAC is built as an imaginary ministry that supports contemporary artistic creation of displaced and refugee Arab artists; a fictitious entity that runs programmes, advises institutions on issues of cultural policy and financial planning, publishes articles, and presents lecture-performances in multiple cities. ETMAC is a unique interdisciplinary project, set between the worlds of institutional making, performance theory, and strategic financial planning.

Introduction

Public cultural institutions, particularly national ministries of culture that are marked by socialist and statist histories, have largely fallen into disrepute. But their histories deserve greater scrutiny, particularly in the Arab world context where the old is becoming new again and statist oversight of culture, relegated to the shadows in the brief period following the end of the Cold War, has found new favour by autocratic regimes. This essay is both a reflection on these historical circumstances as well as an imagining of a different future that adopts the hermeneutics of institutional bureaucracy to subvert and recast cultural institutions as potentially inclusive and liberatory frameworks for collective action. Although the dynamics highlighted here are not limited to or uniquely characteristic of the Arab world, the current geopolitical context of the Arab World lays bare the complex inner mechanics of public cultural institutions and questions of representation. Egypt, ever at the vanguard (for better or worse) of cultural modalities in the region, is particularly instructive and informs both the historicisation of this dynamic as well as our vision for a different future.

The shifting forms of cultural institutions: representation and authority

It was in 1952 that Egypt became a republic, by the popular military coup d’état that later was known as the 1952 revolution. That moment of historical rupture was also an institutional rupture. Culture became both a project of the state and a representative of the state. Artists were largely state workers, and all sorts of necessary infrastructures and bureaucracies were devised to this end. Egypt, being the political force that it was in regional Arab and African politics at the time, became a leader in applying this statist nationalist model of dealing with culture and cultural workers. The first minister to the Egyptian Ministry of Culture was, in fact, an army officer and a military attaché of Egypt abroad. The lines between culture, information, propaganda, and national ideologies were blurred. That first Ministry of Culture was officially named ‘The Ministry of Culture and National Guidance’.

That model took off in the region and its echoes were seen in Syria and Iraq. Pan-Arab initiatives were created, and Non-Allied Movement (NAM) countries came into dialogue. In the 1960s and 1970s, it was more common for an Arab artist to receive a fellowship in a Soviet or Eastern Bloc institution than in the UK or the US. Culture was ideological, and its workers were contained within the newly crafted system. Few were permitted to legally work outside of this system.

In the 1990s, however, the institutional landscape was transformed alongside the broader global realignments of political allegiances and capital that followed the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the fall of the Berlin wall, Egypt’s peace treaty with Israel, president Sadat’s assassination, and the ongoing and overpowering open market policies replacing relics of an Arab socialist past. Cultural institutions reconfigured themselves; and yet, lines of continuity can be traced. Culture in the Arab World continued to evoke what Ngugi wa Thiong’o unpacks in his work Representation and Theatre (wa Thiong’o 1997): “With the emergence of the state, the artist and the state become not only rivals in articulating the laws, moral or formal, that regulate life in society, but also rivals in determining the manner and circumstances of their delivery.” Artists, enmeshed in representational regimes and roles, are automatically enemies of the state unless they work for and with the state, within statist institutions and roles, passing both implicit and explicit censorship and aligning to the expectations of national arts funding bodies.

The open market policies of the post-Nasser, post-NAM world allowed Western philanthropies to establish offices and foundations within the Arabic-speaking region, to seemingly usher artists into modernity, contemporaneity, and democracy all at once. Whether these were contemporary dance workshops for informal training or cultural management seminars for senior directors of institutions, a new threshold was crossed, and the vectors veered more and more towards the West. With every new economy, new politics transpire.

The circumstances in the Arab world mirrored a broader shift towards privatisation of cultural institutions. In some cases, ministerial portfolios have been delegated to the private sector and to the international donor community in the name of efficiency and cost-effectiveness. This displacement of institutional responsibility effectively removes control of a nation’s cultural life from any semblance of representative governance. At the same time, the privatisation of culture has often proven to grossly over-promise innovation and cost savings, with the same dysfunctional models ‘shopped’ from one country to another by those consultants who have best perfected the art of capturing value. In other cases, ministries have been beset by dysfunction resulting from long-term reductions in funding, broader declines in the competence of civil servants and in the desirability of jobs in the civil service, and a decoupling of public sector job tenure from performance. This has been compounded by a general delegitimisation of the arts as a proper recipient of state support, with the exception of instrumentalising it for political purposes, such as during key moments in the history of the Mubarak era in Egypt, as a tool against rising Islamism (see, Winegar 2010, 189–197). Mubarak’s cultural era invested in rural ‘cultural palaces’ as centres of enlightenment outside of the capital, but essentially they were indoctrination sites of national high culture and a statist centric project to fend off rising islamist activism. The ‘independent scene’ emerging outside of this ministerial context continued to be the new alternative for the artistic communities to exist within a different economy and politics. Consequently, as certain modes of cultural expression found, at least for a time, greater permissiveness, the material conditions of making artistic work and the institutional infrastructure to enable it weakened, with a rapidly growing abyss between the statist and independent scenes.

These transformations had the appearance of a loosening of artistic constraints; however, the state reasserted its right to representational regimes, punishing those who stray outside of the state’s worldmaking practices. For decades, the Arab region saw a revolution in cultural spaces and artistic production that happened outside the context of states or commercial ventures and within the new philanthropic economy of the gift – until Arab governments again began to closely monitor these activities, and started a war on culture outside of the state. Extreme censorship in post-war Iraq, Al-Assad’s forces spying on cultural workers in Syria, and the ongoing crackdown on Egypt’s independent cultural institutions are but a few symptoms of recent wars of representational regimes. The cultural worker is the state’s representative and is given that representative power if she/he fulfils the required ideological criteria. This has been enforced, at times, by new lawsA prime example in the Egyptian context is the recent laws that regulate NGOs since 2017. Under Law 70 of 2017 for Regulating the Work of Associations and Other Institutions Working in the Field of Civil Work, all NGOs are prohibited from conducting activities that “harm national security, public order, public morality, or public health,” vague terms that can be abused to constrain legitimate activity (for further reference, see, Human Rights Watch 2017). and has led to the rapid disintegration of the nascent independent art scene in many Arab capitals.

In this environment, cultural institutions lose their legitimacy in the eyes of cultural producers and intermediaries. Moreover, cultural producers lose a substantial resource base. Precariousness ensues, as producers must seek inconsistent venues and be subject to the vagaries of private commissions. Artistic and cultural production withers. Priceless capacities are lost, both in the ability of the state to effectively support artistic production (through the death of functional bureaucracies) and in the ability of citizens to produce art and culture (through brain drain or the abandonment of production entirely). Over time, priceless artistic and cultural objects themselves are lost through outright destruction, piracy, and sale, or otherwise inexplicable disappearance.

Arab cultural institutions: a study in institutional crisis

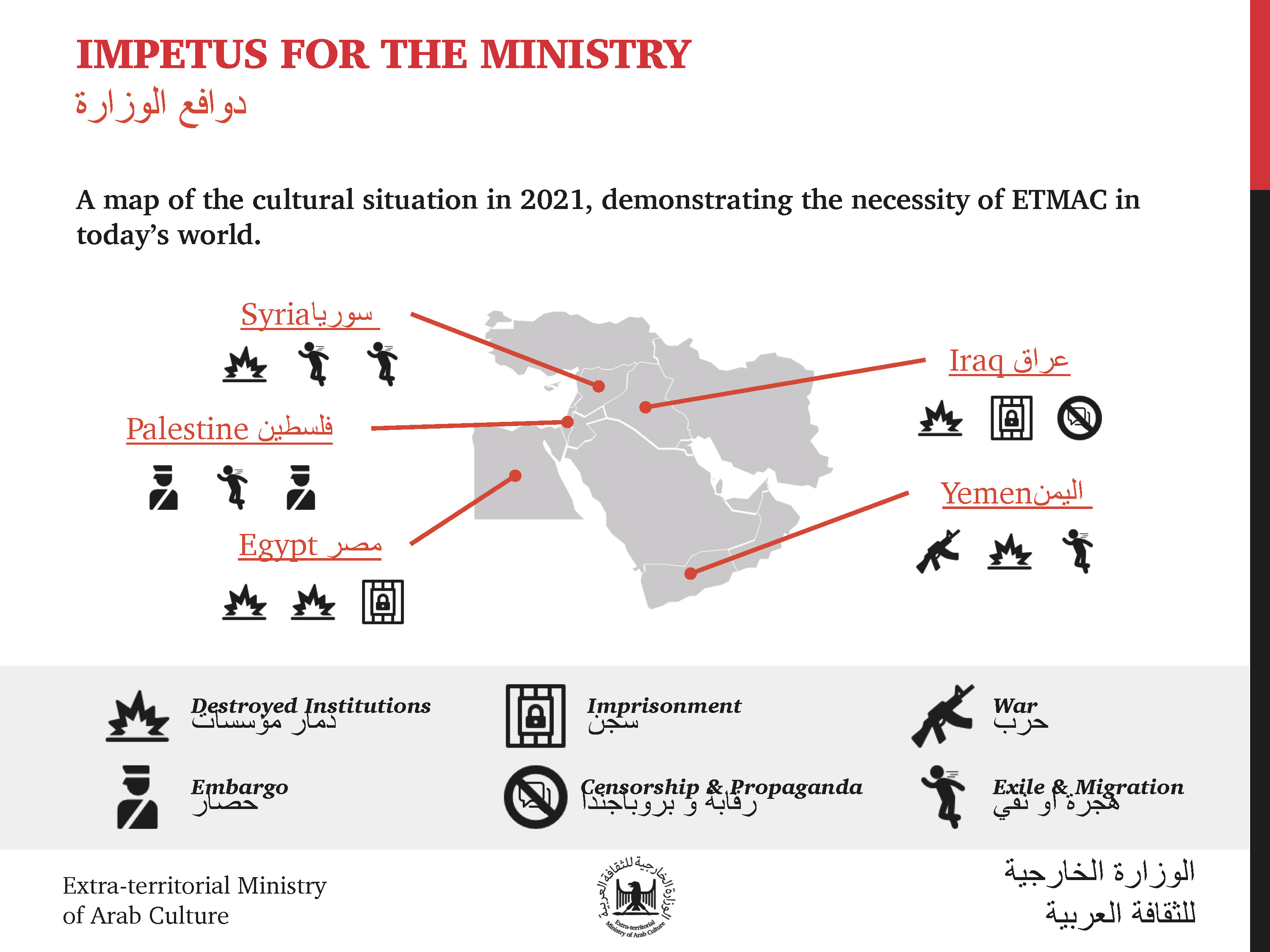

In the Middle East, these trends, pernicious as they are, have been drastically accelerated by geopolitical events. In the wake of the 2011 Arab Spring (and, in the case of Iraq, the 2003 American invasion), a preponderance of Arab Middle Eastern nations have either descended into war, experiencing the functional crippling or even outright destruction of ministries, or have weathered the regional political turbulence through a massive curtailment of freedom of expression, a doubling down on the co-opting of artistic production for propagandistic aims, embargoes of incoming and outgoing cultural production, and the imprisonment of artists and cultural producers who do not acquiesce to regimes (or who are simply convenient scapegoats).

The revolts, revolutions, civil wars, and political unrest of the Arab Spring have often led to a rapid decline in individual freedom, a further rise of autocracy, and a crackdown on political activists and culture workers, while resulting in the largest waves of migration and exile in modern Arab history. Almost ten years ago, unprecedented numbers of Arab citizens – including significant portions of Arab artistic and intellectual communities – moved to Europe and to the US. New niches were created for these cultural workers within European and American art scenes, sometimes as a gesture of political solidarity but occasionally with the trappings of disaster capitalism.

The flight of Arab artists to safe havens is a tribute to the tenacity and bravery of this diaspora. Yet this new model of geographically distributed performance, production, and preservation is deeply problematic. It is contingent upon the benevolence of the host-nations, which themselves are wrought by electoral uncertaintiesIn 2016 to 2017, elections in the United States, Great Britain, Germany, and Austria have resulted in gains by right-wing parties that have campaigned explicitly on confronting a perceived globalist consensus on open trade and borders, and which tend towards cultural nativism. This trend is likely to continue.. Support is often temporary and ad hoc, with migrants’ lives marked by economic precarity. Insofar as this model depends on the benevolence of donors, it is beholden to those donors’ agendas, compromising the autonomy of artists in exchange for survival. Furthermore, these artistic communities are marked as ‘Arab’, and all culture produced within these niches is enjoined to represent Arabness, to be sufficiently Arab. For many artists, this new ideological frame echoes the very conditions they had fled, wherein art must conform to state narratives.

In her book Unmarked: The Politics of Performance, American performance theorist Peggy Phelan argues against the notion of a single, consistent identity. Phelan’s argument challenges the fetishism and imperialism that result from tying representation to planes of visibility, and excluding other forms of fleeting, changeable, and complex forms of representation. Bodies marked as ‘Arab’ in the West are governed as such, and are only allowed a place in discourse (if at all) from these single-narrative, seemingly monolithic identities. And thus are given access to limited and select places on the planes of visibility that shape the politics of performance. Performance here is seen in its larger meaning and not merely within the stage context; indeed, this essay concerns itself with that expanded understanding of performance by thinking of policy and representation performatively. Arab artists in Western cosmopolitan capitals are seen as representatives of the nation-states that they fled and seen as actors that activate a political register in artistic practices. The marked body of an Arab artist could only emerge into artistic discourse and economy by making its mark visible; because it is shaped by a political reality, the artist’s work and voice could only emerge within a political register of practice. Syrian performances are encouraged to reflect on the Syrian Civil War, and those that deviate face the penalty of disinterest and defunding. Palestinian choreography is trapped within curation that foregrounds the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. While a white Western body can speak on behalf of the human experience in abstract or specific ways, a marked Arab body does not have the same luxury. It can only speak from, through, because of, and about its mark and the socio-political conditions of its emergence.

At a time when Arab countries continue to let their creative capital bleed away with the departure, emigration, or exiling of pioneering intellectuals and artists, one wonders about the future of their practices and legacies. As Arab-marked bodies continue to be constrained by the expectations of performing Arabness, the loss of artistic autonomy and genuine freedom of expression increasingly seem too dear a price to pay for safety. We pose a question: can the institution of the ministry of culture be rehabilitated to serve this new diffuse community of art producers and serve as a locus of cultural production outside of the traditional boundaries of the nation? Can it provide spaces that are un-marked by Arabness? Can the institution evolve to meet the needs of an artistic and cultural community that is, at least temporarily, extra-territorial? And can it help to rebuild shattered national ministries on artists’ terms?

Performatively imagining a new kind of institution

ETMAC is a ministry consisting of artists and policy makers from our portfolio countries. 350 part-time and full-time staff distributed across our global offices. The Minister is appointed for four-year terms by a council of Arab diaspora artists representing the countries in the Ministry’s portfolio.

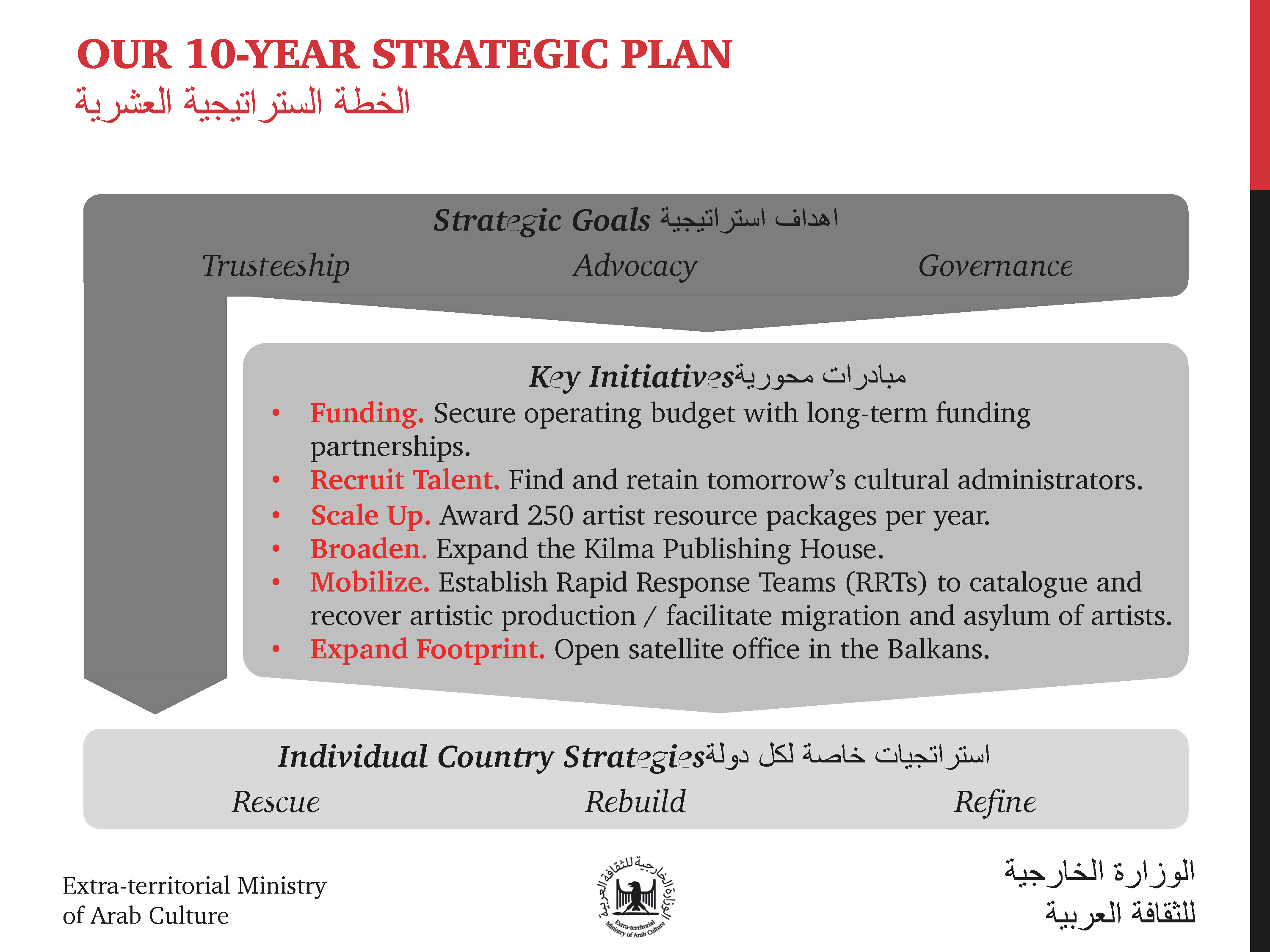

The ‘Extra-Territorial Ministry of Culture’ (ETMAC) is an imagining of what such an institution might look like. We explore the idea through a slide deck presented by two ‘career bureaucrats’ in a performance of deliberate, even banal, bureaucracy (refer to the accompanying figures, presented here with relevant portions of the presentation script). Set in 2021, four years into the future from when the Ministry was created in 2017, the performance imagines a fully formed and operational Ministry, actively administering to a global diasporic community of Arab artists and cultural producers. The deck, a quintessentially bureaucratic communiqué, describes the mission and vision of ETMAC in phrases that, though institutional in their verbiage, are highly focused. The performance uses bureaucratic and corporate mental models – a map of where the Ministry operates, an organisational chart with functional verticals, a ten-year strategic plan – to root ETMAC in actual institutional practice. The functional verticals reflect what we believe to be the most urgent needs of the Arab art community, both globally and in their home countries. A policy advisory vertical produces critical guidance and consultancy to rehabilitate damaged cultural institutions when war ends. A collective bargaining and artist advocacy vertical directly addresses the living conditions and precarity of diaspora artists by channelling resources. A repatriation advisory office assists artists in navigating emigration processes and facilitates the voluntary return of artists and their output to their home countries as conditions improve.

ETMAC was established in haste to meet the challenge of an extraordinary moment in the history of the Arab World; namely, the tumult of the Arab Spring and subsequent collapse and hollowing out of its cultural institutions. Recognising that the furtherance of contemporary Arab art and culture, let alone its preservation, became impossible (and, in some cases, genuinely dangerous) in many Arab nations, ETMAC emerged as a unique ministry of culture – operating outside of any of its portfolio Arab countries and relying on a global diaspora of Arab artists and cultural administrators.

ETMAC is an exercise in political hope, at once utopian and entirely legible. By resorting to dreams, we are pursuing ideas that are not framed by the real conditions of scarcity, fear, unrest, or nomadism. By working on addressing which previous models have failed, we are also able to think about what models could work. Keeping in mind the history of highly centralised decision-making from statist institutions, ETMAC was deliberately created to be decentralised and displaced. With departments and branches in various cities around the world, the Ministry aims to disperse the decision-making process and to create a viable model of inclusion. Maintaining a distance from representative assemblies or nationalist cultural propaganda, ETMAC is about individual practices. By giving room to individual practices and guaranteeing basic conditions of work, ETMAC can allow culture to be produced and safeguarded, rather than produce culture itself in the sense of existing Arab ministries of culture. The institution thus retreats from a creative or curatorial role and instead operates on levels of policy, financial economy, and logistics. This model is suggested as a way to revisit and problematise the role that ministries of culture have played over decades within the Arabic-speaking region.

At the time of inception of the Ministry, it became clear to its Founding Committee that decentralisation of offices is crucial to the mission and vision. Cities were chosen based on international bids, and on pre-existing Arab diasporas and networks.

We envision a post-local strategic future to what is seen as seemingly local practices. We envision continuing to create methods of protecting Arab contemporary culture, but also allowing it to grow and morph on its own terms and conditions, rather than those dictated by Western funding policies.

The problem addressed by ETMAC is not ideological, but rather economic and practical. How do we create platforms for artists to continue to work when they leave their embattled homelands? And how do we allow for communication between their work and new audiences, as well as continue sustaining a relation to the local scenes ‘back home’?

Governed by conflicts, scarce resources, shuffling power regimes, and crackdowns on critical thinking, the Arab region’s cultural operators are unable to present their work in their homelands. ETMAC comes as a radical institution that proposes extra-territoriality as a way of protecting, promoting, disseminating and archiving Arab contemporary art.

The fictitious ETMAC aims at creating these work conditions in the hope that one day, when artists can voluntarily repatriate to an Arab world more replete with possibility, ETMAC will no longer be needed. It is a unique institution framed by the hope that it will one day cease to exist. Furthermore, it is an institution that is not interested in the permanence of crisis, unlike much of the current economies within which nascent Arab art markets are born outside of the Arabic-speaking world. We continue to see crisis being tied to the presentation of Arab arts in the West, without much attention being paid to aesthetic value or cultural capital that is displaced. While ETMAC critically sees this form of crisis-fetishism within its late capitalist context, the Ministry is not set to fight capitalism nor defend socialist pasts. On the contrary, the Ministry encourages new business models that would enable these artists and practitioners to achieve a certain degree of freedom in their practice outside of their homelands.

Beyond an institutional reality shaped by censorship and fear, our Ministry supports its patrons artistically and also legally against prosecution or deportation on the basis of their critical output. Within an intra-war phase, we would like to assert the need to remember previous mass immigration ruptures and what they have provided to global cultural practices and our collective artistic heritage.

Beyond an institutional reality shaped by censorship and fear, our Ministry supports its patrons artistically and also legally against prosecution or deportation on the basis of their critical output. Within an intra-war phase, we would like to assert the need to remember previous mass immigration ruptures and what they have provided to global cultural practices and our collective artistic heritage.

As we approach the tenth anniversary of the Arab world’s revolutions and witness a second wave of uprisings transpire in Lebanon and Algeria – all amidst a global pandemic that fortifies borders more than ever before – ETMAC thinks of a near future of curiosity, humility, and collaboration in which we organise collectively to survive myriad dangers, whether geopolitical, viral, or climatic.

A performance of ETMAC for AltoFest 2018 in Napoli, Italy. Photo by Marco Pavone. Copyright: Adam Kucharski and Adham Hafez

Each iteration of ETMAC is tailored to the host venue’s institutional and local context. In this instance, ETMAC explored local urban activism against gentrification and ‘touristification’, posing the Ministry as a catalyst for equitable urban regeneration of Napoli, and asking what role a cultural institution – representing Arabs, no less – could have as an amenity and resource to local communities.

‘ETMAC: The Extra-territorial Ministry of Arab Culture’ was developed and created for the conference ‘Modelling public space(s) in culture’ organised in October 2017 by Lokomotiva (Skopje, Macedonia) and curated by Biljana Tanurovska Kjulavkovski, Nataša Bodrožić, and Violeta Kachakova. ETMAC was presented as a lecture-performance during the conference and transformed into a text for the publication MODELLING public space(s) in culture: rethinking institutional practices in culture and historical (Dis) continuities, published by Lokomotiva - Centre for new Initiatives in arts and culture, Skopje, 2018.

The authors Adham Hafez and Adam Kucharski actualised this text for the RESHAPE publication, based on their current research and developments in the region and in the world since 2017.

Copyright: the Authors and Lokomotiva- Center for New Initiatives in Art and Culture

References

wa Thiong’o, Ngugi. 1997. “Enactments of power: The politics of Performance Space”, TDR, Vol. 41, No. 3 (Autumn 1997): 11–30. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Winegar, Jessica. 2010. “Culture is the Solution: The Civilizing Mission of the Egyptian State,” Review of Middle East Studies 43 (2): 189–197.