The best we can. Re-establishing priorities for arts professionals in times of crisis

In recent years, my concerns regarding cultural management evolve around three main issues:

- Our incapacity to reflect on the value of our work, linked to a limited or inexistent knowledge of issues affecting the communities we work for;

- The feeling of helplessness when confronted with big political and social challenges;

- Our incapacity or unwillingness to make the necessary adjustments in order to put our resources into better use.

In Portugal, there is no serious and permanent evaluation of what cultural organisations do. We are not used to thinking in terms of mission and of specific objectives. All too often, the mission is a description of ‘what’ we do and not of ‘why we do it’. Most museums and archives will tell us that their mission is to “collect, preserve, research, exhibit and communicate collections” and most theatres and auditoriums state that their mission is the creation and presentation of artistic works in the fields of theatre, dance, music, performance art, etc. Thus, at a managerial level, there doesn’t seem to be an understanding or clear expression of the place cultural organisations wish to have in contemporary society. This failure is then replicated at different other levels within the organisation, with obvious consequences on the performance and well-being of members of staff.

Defining values

Whenever I give professional training for arts professionals, some colleagues look at me in the beginning either with a dose of indifference or mistrust. They have seen everything, they have done what they could, they have given up. They don’t feel they are heard or taken into consideration at their workplace. As the conversation moves on during the training and we try to reflect on the role of cultural organisations and the importance of what we do, things get tougher. Although many people use adjectives like “good”, “signficant” or “important” when discussing what they do, my insistence on understanding “why” it is good, significant or important is met with blank or confused stares. There is no capacity to analyse why they do what they do and how each one contributes towards the organisation’s greater mission.

This doesn’t come as a surprise. The general management of cultural organisations is investing heavily on intense programming without involving itself and the team into a critical evaluation of this activity. People are asked to execute and not to think. Even those who maintain a flame, soon they get tired and eventually declare defeat. Annual reports may present impressive numbers at the end of the year, but teams are not able to answer the question “So what?”. How can they keep on working when there doesn’t seem to be anything in the horizon?

Within this context, one also becomes aware of how little informed many culture professionals are in what concerns contemporary issues affecting the communities they are part of and work for. In a meeting that took place a few months ago in Lisbon – involving artistic directors, actors, managers, colleagues working in education and students – most of us were feeling somehow numb at the beginning of the day: it was Monday morning and we had woken up to the result of the 2018 Brazilian election. Many were at a loss and seemed to be feeling helpless. The discussion quickly picked up and it was soon business as usual. When participants were asked whether they thought Portugal was immune to the Far-Right and whether they were aware of its actions in public spaces (which in the last year involved small demonstrations in front of a private museum in Lisbon, the National Theatre and different schools), there was silence and the usual blank stare. Nobody said they knew about this and perhaps not everyone understood what the connection was, what it had to do with us and our work. In the months that followed, there were intense conversations in Portugal regarding police violence against black people, attacks against LGBT people, the country’s colonial past and the narratives in school books and museums. None of this seems to affect formal cultural organisations, what they do and how they do it. How can we actually contribute towards the development of critical thinking and the development of imagination, both so much needed in our contemporary societies, if we ourselves are not curious enough and remain cut off from whatever goes on around us?

Getting out of the state of numbness

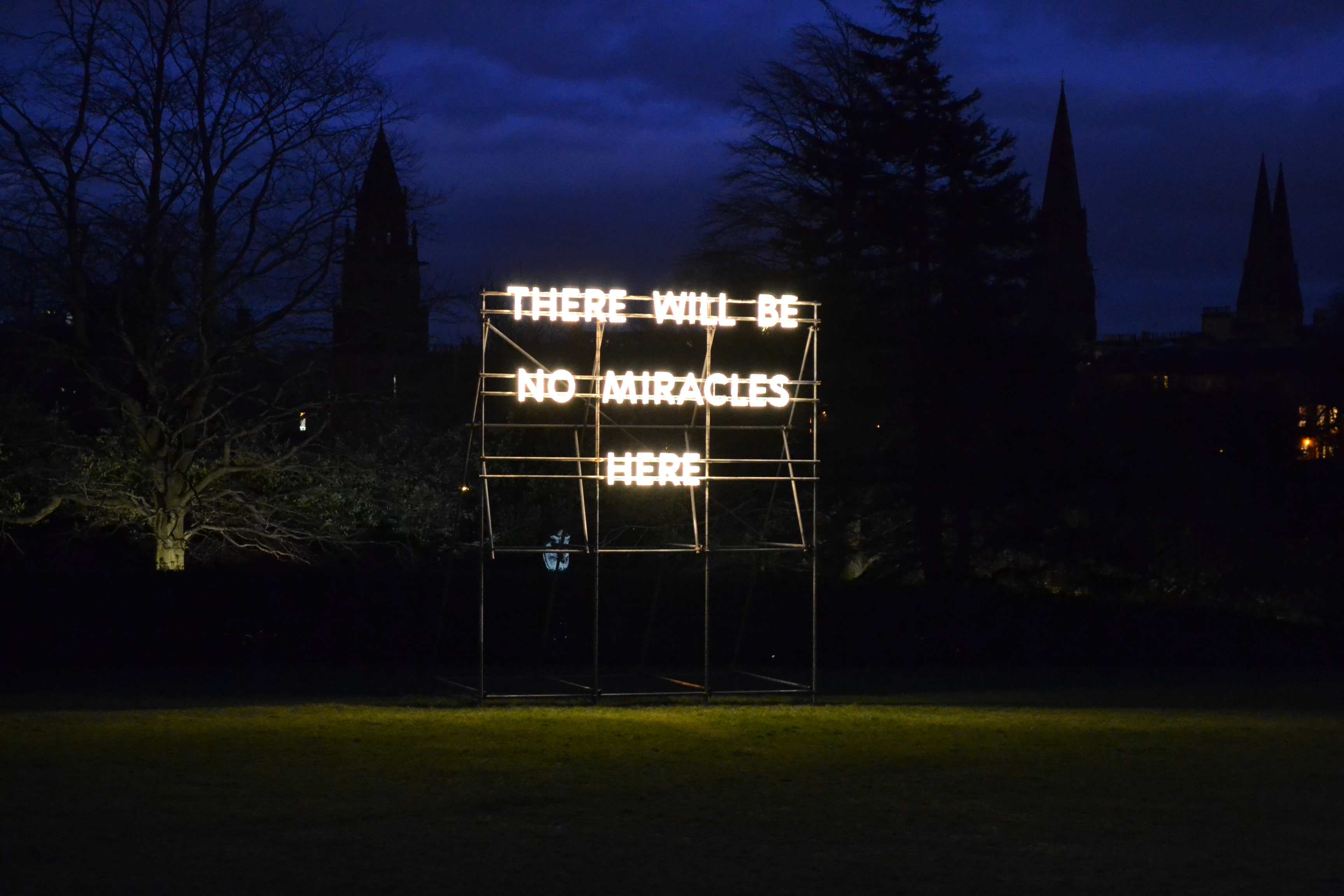

In front of big political and social challenges, the feeling of helplessness is, perhaps, natural. Things look enormous to us. Lacking the conditions to perform our work as well as we would like to, not being motivated and challenged to think critically about what we do and why, being asked to merely execute and to question as little as possible, we tend to feel smaller and smaller. Can there be a way out from this swamp?

At this point - not only because of political and social challenges, but also because of financial shortcomings - I believe we should pause, think and scale down our activity: do less, but be more useful and effective; do less, but be more relevant; do less, but be more creative and happy; do less and make other people happy too. I believe this is a moment where each one of us could rediscover his/her potential and be allowed to use it and do the best he/she can: as an individual, as a professional, as a citizen.

At an individual level, it is necessary that we are more informed and aware of issues which, although they might not affect us directly, they always do, indirectly, because they affect people next to us, people we wish to engage with.

At a professional level, we also need to be more aware of what is going on around us and realise the role we can play in it. There is no point for numerous activities (exhibitions, performances, concerts, talks) if we are not clear as to what we do and why we do it. We might be short of human and financial resources, but, should we be clearer regarding our mission, we could make a better use of the existing ones and become more effective, meaningful and relevant to our communities.

Finally, as citizens, as people being active in the public sphere – both as individuals and professionals – it is urgent that we help create real (non-virtual) public spaces for dialogue. The quality of our democracy depends on the existence of these spaces, not what we sometimes call “safe” spaces, but spaces where there can be a healthy confrontation of ideas and some degree of discomfort. We need to look each other in the eye, we need to listen more and talk less and, through the other, we need to try and get a clearer view of the realities that surround us.

At a recent training, one of the trainees wrote on her evaluation: “When we started working, we all had a big flame burning, but after many years, with many difficulties and being told that our work is not good enough, the flame is gone. I'm leaving today with a renewed flame. My flame had been extinguished for eight years and now it's on again. I can’t wait to go back to work tomorrow and call the colleague who solved a problem I had and ask him how he did it."

This is one person, this is a small thing. But when the wind is favourable, a flame can grow bigger. It is the energy and enthusiasm that keep us going and allow us to do great small things. As professionals, we have to be able to put this energy into effective use, starting by managers, who are responsible for the positioning and performance of whole organisations. Moments and periods of crises may also be moments and periods of great achievements, if we are also able to see them as opportunities, as another chance to do and be the best we can.

Suggested readings:

- Deborah Cullinan (2017), Civic Engagement: Why Cultural Institutions Must Lead the Way

- Maria Vlachou (2019), The great privilege of public life

- Maria Vlachou (2019), “Dividing issues and mission-driven activism: Museum responses to migration policies and the refugee crisis”. In: Janes, R. and Sandell, R. (eds), Museum Activism, Routledge.

- Zofia Cielatkowska (2019), A Political Murder Triggers an Impromptu Action atPoland’s National Gallery of Art

Originally published on Arts Management Quarterly No. 131: Arts Management in Times of Crisis

Happy with what you’ve read? Send us more stuff like this!